Zombies: Ranks of world’s most debt-hobbled companies are soaring, and not all will survive

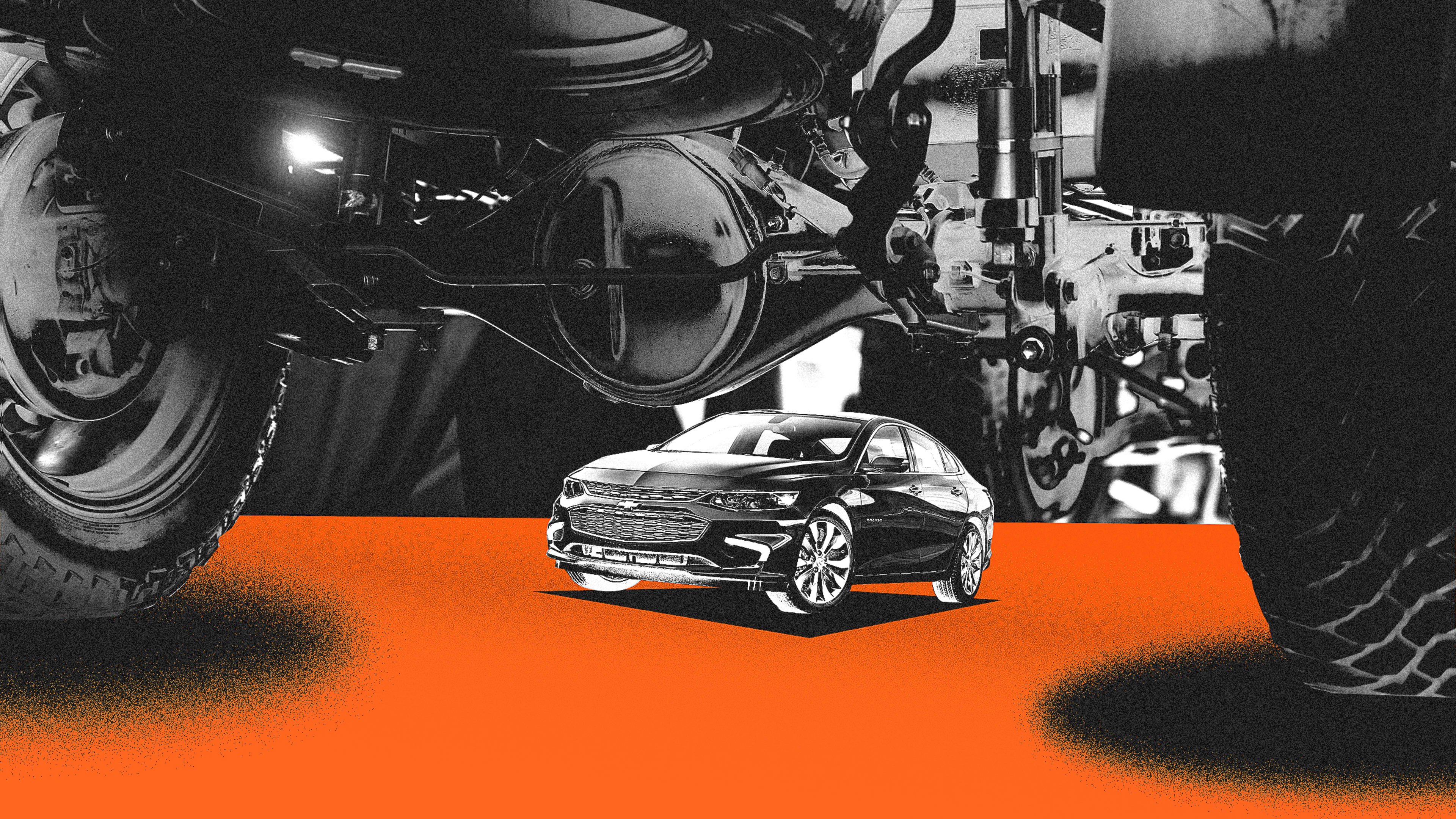

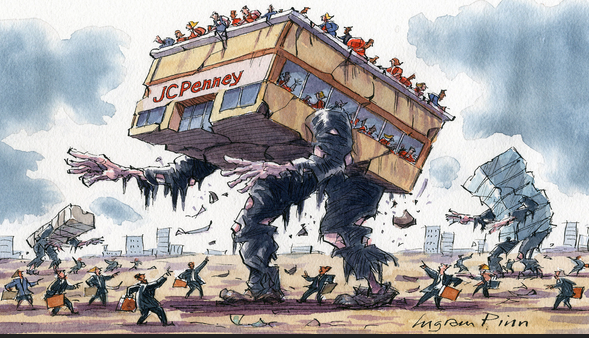

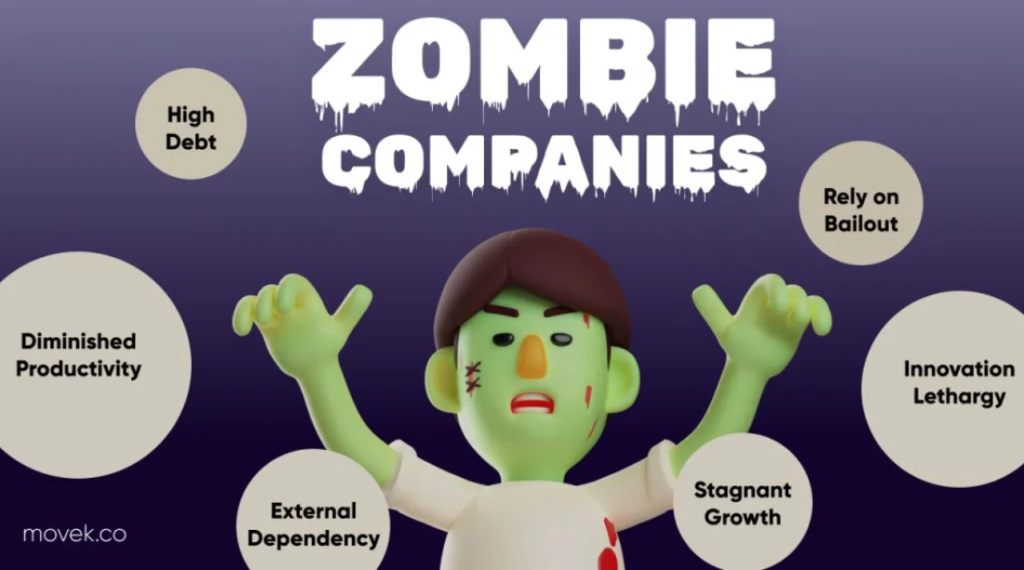

NEW YORK (AP) — They are called zombies, companies so laden with debt that they are just stumbling by on the brink of survival, barely able to pay even the interest on their loans and often just a bad business hit away from dying off for good.

An Associated Press analysis found their numbers have soared to nearly 7,000 publicly traded companies around the world — 2,000 in the United States alone — whiplashed by years of piling up cheap debt followed by stubborn inflation that has pushed borrowing costs to decade highs.

And now many of these mostly small and mid-sized walking wounded could soon be facing their day of reckoning, with due dates looming on hundreds of billions of dollars of loans they may not be able to pay back.

“They’re going to get crushed,” Valens Securities Managing Director Robert Spivey said of the weakest zombies.

Added Miami investor Mark Spitznagel, who famously bet against stocks before the last two crashes: “The clock is ticking.”

Zombies are commonly defined as companies that have failed to make enough money from operations in the past three years to pay even the interest on their loans. AP’s analysis found their ranks in raw numbers have jumped over the past decade by a third or more in Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the U.S., including companies that run Carnival Cruise Line, JetBlue Airways, Wayfair, Peloton, Italy’s Telecom Italia and British soccer giant Manchester United.

An Associated Press analysis found the number of publicly-traded “zombie” companies — those so laden with debt they’re struggling to pay even the interest on their loans — has soared to nearly 7,000 around the world, including 2,000 in the United States.

Takeaways from AP analysis on the rise of world’s debt-laden ‘zombie’ companies

FILE – Trader Michael Milano, center, works with colleagues on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on May 30, 2024. World stocks are mixed on Friday, June 7, 2024, after a steady day on Wall Street as markets anticipate key U.S. jobs data to be revealed later in the day.

To be sure, the number of companies, in general, has increased over the past decade, making comparisons difficult, but even limiting the analysis to companies that existed a decade ago, zombies have jumped nearly 30%.

They include utilities, food producers, tech companies, owners of hospitals and nursing home chains whose weak finances hobbled their responses in the pandemic, and real estate firms struggling with half-empty office buildings in the heart of major cities.

As the number of zombies has grown, so too has the potential damage if they are forced to file for bankruptcy or close their doors permanently. Companies in the AP’s analysis employ at least 130 million people in a dozen countries.

Already, the number of U.S. companies going bankrupt has hit a 14-year high, a surge expected in a recession, not an expansion. Corporate bankruptcies have also recently hit highs of nearly a decade or more in Canada, the U.K., France and Spain.

Some experts say zombies may be able to avoid layoffs, selloffs of business units or collapse if central banks cut interest rates, which the European Central Bank began doing this week, though scattered defaults and bankruptcies could still drag on the economy. Others think the pandemic inflated the ranks of zombies and the impact is temporary.

“Revenue went down, or didn’t grow as much as projected, but that doesn’t mean they are all about to go bust,” said Martin Fridson, CEO of research firm FridsonVision High Yield Strategy.

For its part, Wall Street isn’t panicking. Investors have been buying stock of some zombies and their “junk bonds,” loans rating agencies deem most at risk of default. While that may help zombies raise cash in the short term, investors pouring money into these securities and pushing up their prices could eventually face heavy losses.

“We have people gambling in the public markets at an unprecedented level,” said David Trainer, head of New Constructs, an investment research group that tracks the cash drain on zombies. “They don’t see risk.”

WARNING SIGNS

Credit rating agencies and economists warned about the dangers of companies piling on debt for years as interest rates fell but got a big push when central banks around the world cut benchmark rates to near zero in the 2009 financial crisis and then again in the 2020-21 pandemic.

It was a giant, unprecedented experiment designed to spark a borrowing binge that would help avert a worldwide depression. It also created what some economists saw as a credit bubble that spread far beyond zombies, with low rates that also enticed heavy borrowing by governments, consumers and bigger, healthier companies.

The difference for many zombies is they lack deep cash reserves, and the interest they pay on many of their loans is variable, not fixed, so higher rates are hurting them right now. Most dangerously, zombie debt was often not used to expand, hire or invest in technology, but on buying back their own stock.

These so-called repurchases allow companies to “retire” shares, or take them off the market, a way to make up for new shares often created to boost the pay and retention packages for CEOs and other top executives.

But too many stock buybacks can drain cash from a business, which is what happened at Bed Bath & Beyond. The retail chain that once operated 1,500 stores struggled for years with a troubled transition to digital sales and other problems, but its heavy borrowing and decision to spend $7 billion in a decade on buybacks played a key role in its downfall.

Those buybacks came amid big paydays for top management, which Bed Bath & Beyond said in regulatory filings were intended to align with financial performance. Pay for just three top executives topped $140 million, according to executive data firm Equilar, even as its stock sunk from $80 to zero. Tens of thousands of workers in all 50 states lost their jobs as the chain spiraled to its bankruptcy filing last year.

Companies had a chance to cut their debt after then-President Donald Trump’s 2017 tax overhaul slashed corporate rates and allowed repatriation of profits overseas. But most of the windfall was spent on buybacks instead. Over the next two years, U.S. companies spent a record $1.3 trillion repurchasing and retiring their own stock, a 50% jump from the prior two years.

SmileDirectClub went from spending a little over $1 million a year on buying its own stock before the tax cut to spending $780 million as it boosted pay packages of top executives. One former CEO got $20 million in just four years. Stock in the heavily indebted teeth-straightening company plunged before it went out of business last year and put 2,700 people out of work.

“I was like, ‘How did this ever happen?’” said George Pettigrew, who held a tech job at the company’s Nashville, Tennessee, headquarters. ”I was shocked at the amount of the debt.”

Another zombie, JetBlue, suffered problems felt by many airlines, including the lingering impact of lost business during the pandemic. But it also was hurt by the decision to double its debt in the past decade and purchase hundreds of millions of dollars of its own stock. As interest costs soared and profits evaporated, that stock has dropped by two-thirds, and JetBlue has not made enough in pre-tax earnings to pay $717 million in interest over four straight years.

JetBlue said the AP’s way of screening for zombies isn’t accurate for airlines because big purchases of aircraft “are an intrinsic part of the business model” and don’t reflect an airline’s true health. The company added that it’s been shoring up its finances recently by cutting costs and putting off purchases of new planes. JetBlue also hasn’t done a major stock buyback in four years.

In some cases, borrowed cash has gone straight into the pockets of controlling shareholders and wealthy family owners.

In Britain, the Glazer family that owns much of the Premier League’s Manchester United soccer franchise loaded up the company with debt in 2005, then got the team to borrow hundreds of millions a few years later. At the same time, the family had the team pay dividends to shareholders, including $165 million to the Glazers themselves, while its stadium, the Old Trafford, fell into disrepair.

“They’ve papered over the cracks but we’ve been in decline for more than a decade,” fan lobbying group head Chris Rumfitt said after a recent downpour sent water cascading from the upper stands in what spectators dubbed “Trafford Falls.” “There have been zero investments in infrastructure.”

The Glazers, who separately own the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, recently brought in a new part owner at Manchester United who has promised to inject $300 million into the business. The stock is falling anyway, down 20% so far this year to $16.25, no higher than it was a decade ago.

Manchester United declined to comment.

Zombie collapses wouldn’t be so scary if robust spending by governments, consumers and larger, more stable companies could act as a cushion. But they also piled up debt.

The U.S. government is expected to spend $870 billion this year on interest on its debt alone, up a third in a year and more than it spends on defense. In South Korea, consumers are tapped out as credit card and other household debt hit fresh records. In the U.K., homeowners are missing payments on their mortgages at a rate not seen in years.

A real concern among investors is that too many zombies could collapse at the same time because central banks kept them on life support with low interest rates for years instead of allowing failures to sprinkle out over time, similar to the way allowing small forest fires to burn dry brush helps prevent an inferno.

“They’ve created a tinderbox,” said Spitznagel, founder of Universa Investments. “Any wildfire now threatens the entire ecosystem.”

TIME RUNNING OUT?

For the first few months of this year, hundreds of zombies refinanced their loans as lenders opened their wallets in anticipation that the Federal Reserve would start cutting in March. That new money helped stocks of more than 1,000 zombies in AP’s analysis rise 20% or more in the past six months across the dozen countries.

But many did not or could not refinance, and time is running out.

Through the summer and into September, when many investors now expect the first and only Fed cut this year, zombies will have to pay off $1.1 trillion of loans, according to AP’s analysis, two-thirds of the total due by the end of the year.

For its calculations, the AP used pre-tax, pre-interest earnings of publicly-traded companies from the database FactSet for both years it studied, 2023 and 2013. The countries selected were the biggest by gross domestic product: the U.S., China, Japan, India, Germany, the U.K., France, Canada, South Korea, Spain, Italy and Australia.

The study did not take into account cash in the bank that a company could use to pay its bills or assets it could sell to raise money. The results would also vary if other years were used due to economic conditions and interest rate policies. Still, studies by both the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements, an organization for central banks in Switzerland, generally support AP’s findings that zombies have risen sharply.

Most of the publicly traded companies in the countries studied — 80% of 34,000 total — are not zombies. These healthier companies tend to be bigger with more cash, and many have reinvested it in higher-yielding bonds and other assets to make up for the higher interest payments now. Many also took advantage of pandemic-era low rates to refinance, pushing out repayment due dates into the future.

But the debt hasn’t gone away, and could become a problem for these companies as well if rates don’t fall over the next few years. In 2026, $586 billion in debt is coming due for the companies in the S&P 1500.

“They aren’t on anyone’s radar yet, but they are a hurricane. They could be a Category 4 or Category 5 if interest rates don’t go down,” Valens Securities’ Spivey said. “They’re going to lay people off. They’re going to have to cut costs.”

Some zombies aren’t waiting.

Telecom Italia struck a deal last year to sell its landline network but debt fears continue to push down its stock, so it has moved to put its subsea telecom unit and cell tower business up for sale, too.

Radio giant iHeartMedia, after exiting bankruptcy five years ago with less debt, is still struggling to pay what it owes by unloading real estate and radio towers. Its stock has fallen from $16.50 to $1.10 in five years.

Exercise company Peloton Interactive has laid off hundreds of workers to help pay debt that has more than quadrupled to $2.3 billion in just five years even though its pretax earnings before the new borrowing weren’t enough to pay interest. Stock that had soared to more than $170 a share during the pandemic recently closed at $3.74.

“If rates stay at this level in the near future, we’re going to see more bankruptcies,” said George Cipolloni, a fund manager at Penn Mutual Asset Management. “At some point the money comes due and they’re not going to have it. It’s game over.”

___