RUSSIA IS OUR ENEMY AND OUR NEEDED FRIEND; AGAIN CONNECTED AT THE HIP TO RUSSIA ON URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER DEVELOPMENT!

Since Russia invaded Ukraine , several packages of sanctions targeting Russia’s lucrative energy industry (mostly oil, gas, and coal) have been introduced by the United States, the European Union, and other Western nations. These countries are also undertaking efforts to wean themselves off their dependency on Russian energy supplies.

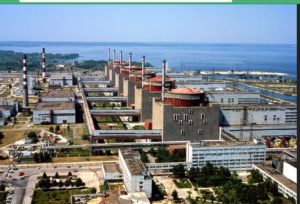

picture of zaparoja nucl

picture of zaparoja nucl

After shelling occurred near Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhya power plant, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy called on the international community to come up with a stronger response and ban Russian imports from yet another sector: nuclear power. But blocking and replacing Russia’s deliveries of uranium, reactors, and nuclear technology to the rest of the world is easier said than done.

Here’s how Russia plays a crucial role in the world’s nuclear cycle.

It’s Not Just About Mining

Russia is among the five countries with the world’s largest uranium resources. It is estimated to have about 486,000 tons of uranium, the equivalent of 8 percent of global supply.

Yet, the country is a relatively small producer of raw uranium. In 2021, it produced just about 5 percent of the world’s uranium from mines.

However, uranium mining is just one piece of the nuclear process. Raw uranium is not suitable as fuel for nuclear plants. It needs to be refined into uranium concentrate, converted into gas, and then enriched. And this is where Russia excels.

In 2020, there were just four conversion plants operating commercially — in Canada, China, France, and Russia. Russia was the largest player, with almost 40 percent of the total uranium conversion infrastructure in the world, and therefore produced the largest share of uranium in gaseous form (called uranium hexafluoride).

The same goes for uranium enrichment, the next step in the nuclear cycle. According to 2018 data (the latest available), that capacity was spread among a handful of key players, with Russia once again responsible for the largest share — about 46 percent.

Therefore, Russia is a significant supplier of both uranium and uranium enrichment services. According to the latest available data, the European Union purchased about 20 percent of its natural uranium and 26 percent of its enrichment services from Russia in 2020. The United States imported about 14 percent of its uranium and 28 percent of all enrichment services from Russia in 2021.

Did Someone Say Nuclear Reactors?

Nuclear reactors made in Russia are known as VVER — an abbreviation for the Russian vodo-vodyanoi enyergeticheskiy reactor (water-water energetic reactor). These reactors use water both as a coolant and as a moderator and were originally developed in the Soviet Union. There are several versions of VVERs (such as the VVER-440 and VVER-1000), with the volume of power being one of the significant differences.

Currently, there are 11 countries where various types of VVERs are operating, including Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Finland. On top of that, other countries such as Egypt, Turkey, and Argentina currently have these reactors under construction or plan to build them.

Russia is considered the world leader when it comes to the export of nuclear plant development. Between 2012 and 2021, Rosatom initiated construction of 19 nuclear reactors; 15 of these were initiated abroad. That is far more than the next most prolific providers: China, France, and South Korea. Although China started building 29 reactors during the same period, only two of them were initiated abroad. France started building two reactors abroad, and South Korea four.

Don’t Forget The Fuel

To keep the reactors operating, plants need a regular supply of nuclear fuel — usually a certain type of fuel. And this is where another level of dependency on Russia can be observed. Although there are several suppliers on the market, the Russian TVEL Fuel Company is currently the only authorized supplier of fuel needed for VVER-440s.

Therefore, certain countries rely on Russian deliveries and could risk temporarily halting operations at their facilities. For example, Slovakia has four of these nuclear reactors; the Czech Republic has two.

Westinghouse, an U.S. nuclear power company, is already seeking ways to offer alternative fuel in Europe, but it will take some time to get all the licenses and approvals. In addition, there are concerns that fuel from the United States might be more expensive, and it is unclear how Westinghouse would handle the waste-management system.

Russia is also able to supply high-assay low-enriched uranium (also known as HALEU). It is a type of fuel that will be needed for more advanced reactors that are now under development by many companies across the United States. The main difference from the fuel that is currently being used is the level of uranium enrichment. Instead of up to 5 percent uranium-235 enrichment, the new generation of reactors needs fuel with up to 20 percent enrichment.

According to the American Office of Nuclear Energy, HALEU availability is crucial for the development and deployment of reactors. The fuel is now available in the United States in limited quantities, and Washington is seeking options to fund research and development of new fuel sources. At the moment, the only supplier able to provide the fuel on a commercial scale is Russia’s Tenex (owned by the Russian state-owned company Rosatom).

Looking For New Markets

Selling nuclear technology is also part of Russia’s effort to gain influence and reap profits in countries that are new to nuclear energy. One of the reasons countries want to cooperate with Russia is that it offers a “whole package” solution. Russia can not only build a nuclear plant and supply fuel, but it also trains local specialists, helps with safety questions, runs scholarship programs, and disposes of radioactive waste.

However, offering attractive loans is probably Russia’s most powerful tool. These loans are usually backed by government subsidies and cover at least 80 percent of construction costs. For example, Russia has already lent $10 billion to Hungary, $11 billion to Bangladesh, and $25 billion to Egypt — all to build nuclear power plants.

Russia has operating nuclear reactors in 11 countries, and more are under construction or being planned. Besides that, Russia has also signed either memorandums of understanding or intergovernmental agreements with at least 30 countries around the world, mostly in Africa. These serve as a declaration of interest in nuclear technology or set an intention to cooperate on the building of nuclear plants, respectively.

Some experts warn that African countries might not be ready for nuclear power, but Russia argues that the technology represents an answer to the continent’s increasing demand for electricity. It is also worth noting that African countries represent the largest voting bloc in the United Nations, which might be another reason for Russia to strengthen its ties in the region.

On August 27, Budapest confirmed that Russia’s Rosatom will start building two new nuclear reactors in Hungary. This information came amid mutual accusations by Ukraine and Russia of shelling Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhya nuclear plant. Zelenskiy has warned of the threat of a radiation leak and accused Russia of “nuclear blackmail.” Meanwhile, Russia blocked the adoption of a final document after a monthlong UN review of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, saying it lacked “balance” amid its criticism of Russia’s occupation of Zaporizhzhya.

The last remaining nuclear power plant in California is in DIABLO CANYON.

The USA can provide the needed Nuclear Power generation and expand it, but it needs RUSSIA!!!! The world is truly interdependent.

)President: “No Science Behind Phase-Out of Fossil Fuels”.

)President: “No Science Behind Phase-Out of Fossil Fuels”.

General Motors, the American industrial icon, who was the envy of its competitors for decades, has now been taken over by woke management pandering to the likes of the climate change fanatics-and right down a rabbit hole of future predictable losses and corporate destruction.

General Motors, the American industrial icon, who was the envy of its competitors for decades, has now been taken over by woke management pandering to the likes of the climate change fanatics-and right down a rabbit hole of future predictable losses and corporate destruction.